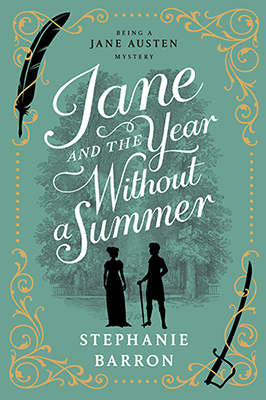

Jane and the Year Without a Summer

“What do you consider the most likely result of Charles’s misfortune?” I asked my brother quietly.

Edward was warming his hands at the fire in the dining parlour. We had just risen from the table, having enjoyed a repast of fresh lamb brought especially from Godmersham, his Kentish estate. My mother’s vegetable garden had provided new peas, and the cellar some of last year’s potatoes. We had avoided canvassing poor Charles’s news. But now I lingered after the others had removed to the sitting-room, from a desire to know my elder brother’s mind.

“From his account, Charles ought not to be blamed,” Edward replied, knitting his brows as he gazed into the glowing coals. “He states precisely that the Phoenix foundered in a hurricane—and due to the carelessness of the native pilots, who drove her onto the rocks.”

Phoenix was the name of my brother’s frigate; he had been in command of her some years. “He cannot be blamed, to be sure,” I agreed, “but as captain, can he not be held responsible?”

A faint and somewhat grim smiled flickered over Edward’s lips. “How like you, Jane, to cast the dilemma in words of dueling precision! Yes, Charles will certainly be held responsible—and accountable—for the wreck of the Phoenix, blameless tho’ he be. Indeed, he may never get another ship.”

I sighed in vexation. “That is unjust!”

“Charles advises us he must appear before an Admiralty Board of Review. When His Majesty’s vessels go to the bottom, with or without their crews, such authority is empaneled to mete out guilt—as well as punishment. Being unable to flog, demote, or demand restitution of the native pilots long since set down in Smyrna, the Admiralty may find satisfaction in ordering the frigate captain—in this case, Charles—permanently ashore.”

I shivered, and joined Edward on the hearth; despite the advanced date in May, the evening was drawing in with a chill, and the blight of further rain. “I suppose now the Monster is at St. Helena and the war over, Charles is unlikely to win further prizes or advancement in any case. But, oh, Edward—that his career should founder with his ship! If he should be stripped of rank—struck from the Navy List and the pay that comes with it—what is to become of his little girls?”

My brother laid his arm about my shoulders and drew me close. “We must hope for better, my dear. Do not be entirely cast down. Think how Charles is everywhere admired by his fellows! How otherwise unblemished has been his decade of service. How much praise was heaped upon him for his blockade of Marshal Murat, at Naples, two years since, commanding this very same Phoenix! And Charles is an excellent witness on his own behalf—so clear in his histories, so meticulous in his ordering of events. Only consider the case he makes for himself in this letter.”

Edward wished to persuade me out of my fears, but I could not shake off worry. Our whole family has suffered too much ill-fortune this winter for optimism to seem advisable. “But will this panel of admirals credit his account?”

“If they possess either conscience or understanding.”

“Let there be one man among them who regards Charles as his enemy,” I mused, “— from pettiness, jealousy, or excessive regard for a rival in the Service—and the temptation to see our brother ruined must be great.”

“Do not borrow trouble, Jane.” Edward met my gaze, his own sombre. “It cannot improve Charles’s chances, and will only disorder your sleep. You must endeavour to divert your mind, my dear—and await the outcome as our sister Cassandra does: with cheerfulness and sanguine hope.”

“What is this, Edward?” I rallied him. “Enjoining me to imitate Cassandra—who performs every duty in life with a grace that is truly Angelic—when you know me constitutionally incapable? I shall never have her goodness!”

But my brother did not smile; instead, he searched my countenance. “You take too much upon yourself, Jane—the cares of the whole family. I confess I have wished I might spare you even a part of it. Will you consider returning into Kent with Fanny and me, so soon as Wednesday? Let us cosset you for a little. I am sure a month at Godmersham would do you good. You might even write, without interruption!”

I hesitated, then glanced over my shoulder towards the sitting-room. The sound of Fanny’s gentle murmur drifted along the passage. “That is very kind in you, Edward, but as it happens, I have a different scheme in hand, and mean to act upon it immediately.”

His eyes narrowed in speculation. “What sort of scheme?”

“One of heedless dissipation and stolen freedom,” I confided. “Do but think, Edward! I mean to spend an entire fortnight away from home, with only Cassandra for company!”

He looked bewildered, as well he might; we Austen ladies rarely quit Chawton unless it is to visit one of our brothers. “But where are you going, Jane?”

“Cheltenham Spa!” I told him triumphantly. “We mean to take lodgings, and stroll with the ton about the Arcade, and eat ices and drink French wine, and be above vulgar economy! For two whole weeks, Edward. And you are not to be worrying that we will be a charge upon Mamma’s purse, or hanging on your sleeve. I mean to treat Cassandra. A small part of my profits from Emma should meet the expence handsomely.”

© Stephanie Barron