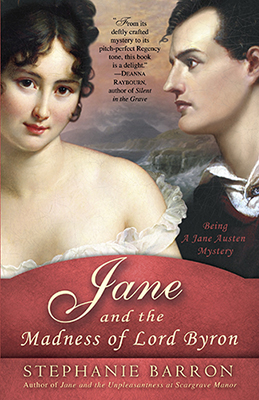

Jane and the Madness of Lord Byron

Chapter 1: Summons From London

25 April 1813

Sloane Street, London

Mr. Wordsworth or Sir Walter Scott should never struggle, as I do, to describe Spring in Chawton: the delight of slipping on one’s bonnet, in the fresh, new hour before breakfast, and securing about one’s shoulders the faded pelisse of jaconet that has served one so nobly for countless Aprils past; of walking alone into the morning, as birdsong and tugging breezes swell about one’s head; of the catch in one’s throat at the glimpse of a fox, hurrying home to her kits waiting curled and warm in the den beneath the Park’s great oaks. Spring—in all its rains and clinging mud, its sharp green scents full-blown on the nose, and a newborn foal in the pasture below the Great House!

And in this glorious season, too, a splendid change has come upon the little Hampshire village I call my own—for my elder brother, the rich and distinguished Mr. Edward Austen Knight, as he and all his numerous progeny must now style themselves, having acceded to his benefactor’s surname as well as his estates in Kent and Hampshire—has descended in state upon Chawton Great House, with his full retinue of trusted servants, under-gardeners, grooms, coachmen and what I am pleased to call Edward’s Harem: a hopeful clutch of motherless daughters, most too young to marry and still at home.

Edward intends to spend the better part of the summer in the antiquated pile that once was let to our dear neighbours, the Middletons, Mr. John Middleton having determined to give up the place when his treaty was run. While the Austen Knights idle away June and July in Hampshire, their principal seat—Godmersham Park, in Kent—will submit to refurbishment, the interiors having grown sadly shabby without Edward’s late wife’s care. It is quite a treat to have one’s relations—and all the elegancies of table, coach and society—but a stone’s throw from one’s door; and I spun many happy webs for myself that bright April morning, as I walked through the meadows, and listened to the song of a blackbird hidden somewhere in the hedgerow. Edward’s eldest daughter, Fanny, is full twenty years old—and although a trifle subdued for my taste, and possessed of starched notions quite appalling in one so young, she must be adjudged a welcome addition to the Cottage circle, whenever she may venture through the village in search of trifles and laughter. It was possible, I thought, that Martha Lloyd and I between us might be of use to poor dear Fanny, in enlarging her spirit and mind—or at the very least, her capacity for wit. There is nothing so quelling in a young woman, I find, as a want of humour; but much must be forgiven the girl—she was thrust too young into the role of Mother, when Elizabeth died. Fanny cannot have been more than thirteen, then; and at twenty, must feel already as though she has lived two lifetimes, in managing her father’s household. She is certain to find Chawton unutterably dull, however; the Assemblies in Alton are not such as she has been used to, in the elegant Kentish circle she frequents. Was there, I wondered, any young man in the neighbourhood capable of engaging her interest?

Considering and discarding the various scions of local families as I walked amid the dew-laden grass, I was full of pleasurable schemes that dreadful morning. Once Fanny was dismissed as too dear a prize for Alton’s youth, my mind revolved the various attractions of an altogether different cut of gentleman—one Henry Crawford: for I have reached a most delicious point in the writing of my third novel, which is to be called Mansfield Park, when I must decide whether another Fanny (a sober and rather humourless young woman entirely of my own invention, though not quite my niece), is to make the roguish creature the Happiest of Men, or cast him into the Depths of Misery at a single word.

I had turned toward home after a brisk half hour of exercise and rambling thought; when all at once it was as though a cloud moved swiftly across the sun, and my pleasure in the day was blotted out. The very air felt chill. I stopped short a good thirty paces from the Cottage door, a feeling of deepest dread in my heart—and for why? Only that a handsome chestnut hack was tethered to the post in the lane, one I recognised as my nephew Edward’s mount. Why should a morning call, even one paid so unfashionably before breakfast, have the power to stop my heart?

I ran the final distance to the door.

My brother’s eldest son and heir was standing before the fire, dressed not for hacking about the countryside in buckskins and boots, but for Town; his cravat meticulously tied, shirt points terrifyingly starched; a striped waistcoat trimly buttoned over primrose-coloured pantaloons. An Oxford lad of nearly nineteen, he had styled himself a Corinthian of the First Stare; and it was this unwonted grandeur, as well as the expression of scared dignity on his young countenance, that informed me my heart had not erred. Disaster was in the air.

“What is it?” I whispered.

Cassandra came to me then, and enfolded me in her arms.

“An Express from Henry, to the Great House,” she said.

“Has she gone?” I faltered. “And none of us aware?”

Edward cleared his throat. “Not quite gone, Aunt. But failing, Uncle Henry says. She is asking for you, I believe. Father says you are to travel up to London as soon as may be—in his chaise—and I am to bear you company.”

“Edward!” I stared at him. “I am sure you should much rather be hunting rabbits on such a fine morning.”

“So I should, ma’am,” he stammered, “but under the circumstances—no exertion too great—should consider it an honour—wish most earnestly that you will accept my escort.” He bowed stiffly, his face flushing with embarrassment. “Not the thing, you know—lady travelling entirely alone. Might very well be offered an intolerable insult. Besides, m’father commands it.”

Edward, whom I cared for and cajoled so many years since, when his own mother died—to be offering me escort! I understood, then, the punctiliousness of his manner and dress. He was representing his House—and paying off a debt of gratitude. I should be churlish to protest further; and besides, the hour was already advancing.

I uttered not another word, but dashed upstairs to throw what swift provision I could into a carpet bag. My beloved Eliza, Comtesse de Feuillide, wife of Mr. Henry Austen of Sloane Street—was dying. It seemed far too bitter a truth for Spring.

When did she first apprehend her mortal sickness, I wondered for the thousandth time as the chaise jolted and swayed over the Hog’s-back an hour later? Was it so early as my descent on London some two years since, for the proofing of the typeset pages of Sense and Sensibility? She suffered then, as I recall, from a trifling cold, and took to her bed on the strength of it; but surely that was a deliberate indulgence, to avoid the necessity of attending Divine Service of a particular Sunday?

Eliza was never very fond of Divine Service; she had seen too much of Sin, to place her faith in either repentance or redemption; and she felt certain that the clergy were the very last sort of men to lecture their brethren—indeed, she declared the whole pious enterprise an essay in hypocrisy. Eliza preferred to live her life and leave her neighbours to live theirs, without the benefit of unwonted advice or inspection; and on the whole, I confess I admire her philosophy. There is a great deal of disinterested benevolence in it.

If not April of 1811, then, the illness came upon her soon after: a mass in the breast, that grew until it might almost have formed another—with tenderness, increasing pain, and suppuration. She had watched over her mother’s dying of the selfsame malady, years since. She recognised the Enemy.

My incorrigible Eliza. My gallant friend. A word for gentlemen of high courage—but courage she brought to this final battle, knowing full well she would never triumph. The summer months of 1812 she spent in travel—relished two weeks in the sea air of Ramsgate in October—wished me joy of Pride and Prejudice’s sale to Mr. Egerton in November (which met with decided success at its publication this winter among the Fashionables of the ton!)—and by Christmas was rapidly declining.

And Henry?

I might have said that he has not the mind for Affliction; he is too busy; too active; too sanguine. All the increasing cares of banking—my naval brother Frank being now a partner in Henry’s concern—and the activity necessary to a gentleman in the prime of his life, must inevitably attach Henry to the world. Add to this, that Eliza is fully ten years his senior, and that the gradual progression of the disease has offered an interval for resignation and acceptance—and we may apprehend the steadiness with which Henry meets his impending loss. And yet—his summons to me augurs an unquiet mind, a soul in need of comfort. To part with such a companion as Eliza!—Who, though she gave him no child, brought him endless cheer and laughter from the first day he met her, as a boy of fifteen, when she descended a la comtesse on the Steventon parsonage, and dazzled us all within an inch of our lives.

“I believe Uncle Henry intends to give up Sloane Street,” Edward observed as we rolled into Bagshot; “He claims he cannot bear to meet with my aunt’s memory at every stair and corner.”

“Better to remove from London, then,” I returned, “for Eliza shall haunt every bit of it.”

I have known the journey from Chawton to run full twelve hours, when leisure permitted; but we were to have no dawdling luncheon, no walking before the coachman in admiration of April flowers, no pause for fine views as we descended the final stage into the Metropolis. Barely eight hours elapsed from the moment I bade farewell to Cassandra at the Cottage door, until I found myself alighting in Sloane Street.

We met the apothecary, Mr. Haden, on the threshold—Madame Bigeon being on the point of ushering the good man out, as we ushered ourselves within—and paused, despite a scattering of rain, to learn his opinion.

“I fear she is sinking, Miss Austen,” he said somberly. “A matter of hours must decide it. I have left a quantity of laudanum—you are to give her twenty drops, in a glass of warm water, as she requires it.”

“But Eliza detests laudanum!” I cried. “I have known her dreams to become frightful, under its influence.”

“Her agony will be the more extreme without it.” The apothecary doffed his hat to Edward and me, and stepped past us to the street.

“Mademoiselle Jane!” Mme. Bigeon’s elderly voice quavered on the greeting; she gave way that we might enter the hall, her black eyes filled with tears. “At last you are come! I feared—but it is not too late. She sleeps much, yes, but she will wake for you, mon Dieu! Come to her at once!”

With unaccustomed familiarity—such is the strength of feeling in the face of Eternity—the old Frenchwoman grasped my hand and drew me swiftly up the stairs. I could not stay even to loose my bonnet strings; and that I should be aware of such a nothing on the point of seeing Eliza, must be an enduring reproach. I am ashamed to own it.

Mme. Bigeon hesitated before the bedchamber door; it was ajar, so that I could just glimpse the outline of the bedstead, my brother Henry dozing in a straight-backed chair set up against the wall; and the silhouette of Mme. Marie Perigord—the old woman’s daughter and Eliza’s dresser, her constant reminder of all the glories of France that are gone beyond recall. Manon, as she is called, was seated near the bed, her sharp-featured face thrown into relief by the flame of a single candle; in her hand was a small bowl.

And beyond—

Eliza.

Her eyes were closed, her breathing heavy; a few damp locks of hair escaped from her white cap. There was a peculiar odor on the air—a sweet, sickly smell that emanated from the open wound in her breast, and the great tumor lying malevolently there; no amount of warm compresses or fresh linen could blot out the taint.

I crept softly to the bedside, young Edward hesitating behind me.

Manon rose and drew back her chair. “Monsieur—Mademoiselle…I cannot persuade her to take any of the broth. And it is Maman’s best broth, made from a pullet. Five hours it has been simmering on the stove—”

“Hush,” Henry muttered, as he jerked awake. His dazed eyes met mine through the shuttered gloom. “Ah—Jane! You are come at last!”

He rose, and pulled me close; the stale odor of a closed room, and clothes too infrequently exchanged, clung about his person. Henry—who is the nearest example of a Dandy the Austens may claim—had been neglecting himself.

“Praise God you came in time,” he whispered.

“Mademoiselle!” Manon tugged impatiently at my sleeve. “Perhaps you will try? Perhaps she will take some broth from you, hein?”

“What does it matter?” Henry burst out, worn beyond bearing.

“But she must keep up her strength!” the maid protested.

Pointless to observe that strength would avail her mistress nothing, now.

Manon’s face crumpled into a terrible grimace and she began, painfully, to weep, turning away from the awkward crowd of Austens as though we had caught her at something shameful. Mme. Bigeon swept her daughter out of the room, murmuring softly in her native tongue, half-scolding. I had an idea of the maid’s high pitch of nerves, waiting in that darkened chamber through all the hours of a night and day as her mistress’s life slowly ebbed, ears pricked for the sound of a particular set of horses halting in the street below. How like Eliza to hold on to the last, as though she knew I was hastening toward her!

But was she even aware of my presence?

“Dearest,” Henry whispered, bending over Eliza. “Here is Jane arrived from Chawton.”

Her eyelids flickered; the clouded gaze fixed for an instant on my brother’s face, unseeing. How great a change was come upon that sprite, that eager, winning countenance! And how helpless I felt, unable to save her, to forestall the dreaded end!

I took up the bowl of broth and the silver spoon still warm from Manon’s hand, leaned close to my dying cousin, and whispered, “Come, my darling, and try a little—to please your Jane.”

Young Edward returned in his father’s chaise the next morning to Chawton. The rest of us took it in turns to watch with Eliza, although in truth Henry was never from the sick room. He dozed upright in a chair, regardless of whether the Frenchwomen or I were attending upon his wife. For my own part, I snatched at sleep whenever one of the others relieved me—curling fully clothed on the comfortable bed in the best bedchamber. We ate what we could at odd hours, taking cold meat and tea in the breakfast room; Mme. Bigeon had no heart to cook, or rather her cooking was all for Eliza: possets, puddings, coddled eggs that were returned, one by one, untouched on their plates. Through the hours Eliza shuddered, and turned, her mind beset by the demons brought forth in laudanum; and though Henry and I would have stinted her, she suffered too much when the draughts were denied.

What did she mutter, as I leaned over her in the depths of the night? Regret…regret…. Her fingers claw-like at my wrist.

The upright and devout would urge me to believe in a deathbed conversion—some softening of her pagan heart, as the life sped out of her—but I am too well acquainted with the little Comtesse. I regret nothing, Jane, she would wish me to know. Regret nothing. Not the madcap days in Marie Antoinette’s train, or the careless disregard for reputation and finances, the husband lost to the guillotine; not the dashing promenades in Hyde Park with a score of beaux dazzled by her wicked dark eyes. Her dead son she might yearn for—wasted from birth by too many ills—but even Hastings could never figure as cause for regret. She cherished the boy, heedless of a world that declared him little better than an idiot.

She shall sleep beside him soon.

This morning, near dawn, there was a change. The poor roving spirit stilled and her body went slack, the eyes tightly closed. The sound of her laboured breathing mounted until it seemed to fill the whole room—the airless weight of that room, its single candle glowing. Henry’s hand clasped hers, but she seemed insensible of it; and at the last, with barely a flutter of its wings, Death entered the room. She turned her head once on the pillow, toward the window—raised herself slightly—and then fell back, a shell.

I waited, breath suspended. And apprehended that her breathing, too, was done—the very walls listened for it, every window frame strained; no sigh murmured back.

Henry stared at his wife as if expecting her eyes to open. Then he placed her limp hand gently on the coverlet, and rose from his chair.

I would have gone to him; but the look on his face was terrible. He walked without a word from the room, and after a final glance at the still figure at its center, I fled in search of the maids.

30 April 1813

Sloane Street

All week the candles have flickered by her bier in the pretty little salon she loved so well, where her Musical Evenings collected a gay throng and her morning callers were wont to sit; tributes of spring flowers arrive daily from Henry’s colleagues and Eliza’s acquaintance both highborn and low. Lord Moira sent a massive wreath of lilies; but I think I like best the posy of wildflowers offered at the kitchen door, by one unknown fellow Mme. Bigeon assures me was Eliza’s favorite hackney coachman.

Mrs. Tilson—the wife of one of Henry’s partners and a near neighbour—came to call, and sat with me a half-hour in Eliza’s boudoir; I cannot love her, but she forbore to express her displeasure at my sister’s frivolities quite so forcibly as in the past.

Eliza is to be buried at Hampstead tomorrow, beside her mother and son; Manon and I shall wait only for the train of black carriages to depart, before quitting Sloane Street ourselves. The poor maid is quite worn down with nursing Eliza, and could do with a rest in the country—I am to carry her off to Chawton, until Henry comes to fetch her. It shall be a comfort to have the Frenchwoman beside me, merely to dull the edge of grief.

The rain and bitter fog descended upon us today; Spring, it seems, is quite fled. Eliza’s death comes as a presentiment, a weight of dark cloud sitting over the house; we are all of us growing older, Henry and I and the two Frenchwomen.

The Autumn of my life is come—my hopes of happiness long since buried in an unmarked grave—and how long, pray, shall the sun endure, before Winter?

© Stephanie Barron